chinese period of my life (a visit to China pt.1)

China's perfected capitalism, the abundance of creation, and the invisible humans who keep it running

In December and January, I spent over a month in China, across Shanghai, Jingdezhen (the ceramics capital), and Shenzhen (the manufacturing capital). I visited factories and studios, art museums and phone farms, and tiny stalls and bougie stores. I haven’t been in China since 2008, so everything was new and exciting to me. What follows is a condensed breakdown of all the observations I had (of which there are a lot because China just operates so differently compared to every other country I’ve been to). I’m splitting them up into 3 sections: physical culture, digital culture, and craft/creative culture

China is the most capitalist place I have ever been to. It feels so good to be a consumer, especially because prices are so low compared to U.S.. At every restaurant, several servers take care of you, ensuring your tea is never empty and your food comes out instantly. At the malls, employees stand by the door and hold it open for you (even if it can lock into place by itself).

Speaking of the malls, they are the pinnacle of the absurdity of modern Chinese capitalism. A 17-floor climbing wall, a mermaid show in a fish tank, and a hot pot restaurant’s traditional performance for waiting patrons in camping chairs are among the standouts.

Anything that exists is available often at any hour of the day. Want a massage at 11pm? Look up massages on 大众点评 (Dianping) and walk in. Need coffee in between meetings? Order a 美团 (Meituan) to get a scooter to deliver a single-origin pour to your hand as you walk between them.

The morning after going out dancing, I ordered a breakfast feast from bed and it arrived to my door, delivered by a man in an all-yellow outfit and motorcycle helmet by the time I had rolled out, all for much less than I would have paid for a breakfast sandwich in San Francisco.

Because there’s so much technological advances, I assumed that human labor would be automated, too. Instead, I see people everywhere I look—human labor that has exploded to fill the gaps where the automation can’t reach.

So while you can order anything from an app, correcting any mistakes requires human support to call the involved stores to manually adjust. When you book train tickets on trip.com, your request goes to Chinese staff who call the relevant stations to book your ticket. You can find thousands of suppliers online, but the most important business is conducted through WeChat voice messages and over tea next to the factory.

These systems have a massive chain of dependencies that are rigid to a fault, which leaves it up to humans and manual interventions to change anything. In short, it all comes down to “knowing a guy.”

Visiting Shenzhen, I started to understand that creating anything material is not only possible but easy because anything you need can be acquired, affordably and quickly.

I ordered all kinds of materials from Taobao. One of these finds became the basis for a project Kelin and I hacked together called Bumper Phones, in less than 6 hours. The physical good convenience of China combined with the digital good convenience of modern AI-coding tools made creation feel instantaneous. It was the first time the malleability of the physical world felt close to how easy it feels to change the digital. I imagined a universe doubling down on this power, locking into the 996 grind in China, getting delivery for every meal, and creating all the art I’ve wanted to make.

At the factories, I watched thousands of products be born, millions of which will reach people’s homes in the coming weeks and months. The scale of impact that these people have on the world is immense. A said “what I’m doing is nothing in comparison.” We shared a deep existential realization about how much influence you can actually have on people’s lives and each questioned our relationships to scale.

As S and I lay face down getting Dianping massages, we started talking with the masseuses about life in China vs life in America, and one of them remarked 中國太方便了 (”life in China is too convenient”).

China operates in a primitive future: the bleeding edge of technology is incorporated into daily life at unthinkable scale but patched together by an army of human laborers working for meager wages and punishing conditions.1

As much as I enjoyed getting all my material comforts met at any time of day for cheap, I can’t help but wonder if this is how I want to live. There are things that are undeniably good (an affordable and livable society) and things that I’m not sure the cost of but I desperately yearn for in my life (access to any physical material for creative projects). Which things come with the territory, and when is the power worth the sacrifice?

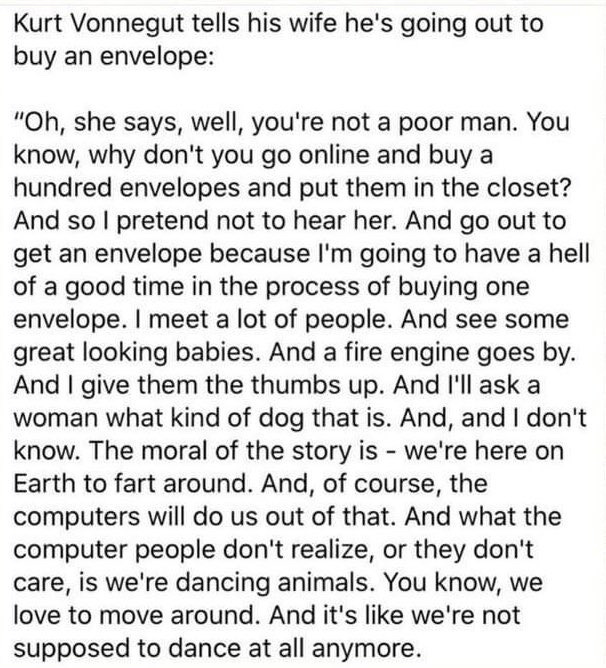

Lately, with each advancement of our machines, I’ve been thinking about this anecdote from Kurt Vonnegut. Convenience is powerful and tempting, especially as a creative who never feels like they have enough time or resources. But I'm not sure we deserve that much power.

I can’t imagine giving up my frictionful everyday human encounters. The inconvenience is the cost we pay to encounter each other, to stumble onto a new discovery, to expand our ways of seeing. These kinds of things can’t be engineered.

Spencer

I have so many thoughts from this trip that it’s hard to condense into just one piece! next time, I’ll talk about the digital culture in China and how it felt to be forced to completely change my digital infrastructure. And then I’ll close reflecting on the culture around and attitude towards craft.

UPDATES

In Internet Sculptures news, I released Touchstone, a companion app for customizing your sculptures (learn more). It feels exciting to create physical objects that will last and also enable you to adapt the digital side to grow with you. I also broke down my launch of the Phone Pillow and reflected on everything I did wrong.

I’m getting closer to getting some public released for my internet movement extension, which will track your browser actions and turn them into art pieces and eventually turn the entire Internet into a shared space. Sign up here to be on the beta!

This dispatch was sent to 1924 inboxes. My writing is always free and open, but I am independently funded and appreciate any support you can offer. Consider sharing this with a friend and becoming a patron (or for those without Github, subscribing on Substack) for the warm & fuzzy feeling of supporting an indie artist (and access to the community & works-in-progress) .

Thank you to the 27 people who supported my independent work with a sponsorship last month.

Unfortunately, the importance of labor doesn’t translate to power. Chinese delivery drivers are famously subject to extreme working conditions and receive financial penalties for being late and getting low reviews. Many artists have created pieces to highlight the humanity of these workers, like Cao Fei’s Whose Utopia showing the lives of factory workers and Out For Delivery, a video game that lets you shadow a food delivery driver in Beijing.

i like it